The Power of Points

When people ask me how I travel so much for so little money, I usually just keep it simple with a one word answer: “Points”. That answer is usually followed by a brief explanation of the concept of travel hacking and how I benefit from it. On more than one occasion, the topic of travel hacking seems to bring on a direct question: “Oh you’re scamming the system?”.

At first I was a bit stunned to hear the question, but then I realized that the person asking the question has little or no idea what it is that I, and others who collect award points, do. They don’t know the time, energy, and dedication that we put into the hobby and how great it feels when the rewards pay off. They probably don’t have a deep understanding of the rewards system, and how they may or may not be supporting that even without their knowledge.

Travel Hacking

To be honest, I don’t really care for the term “travel hacking” but it’s part of what I and others like me do. It’s also a pretty accurate phrase to describe it too. At the most basic level travel hacking is doing anything to reduce or eliminate the cost of travel. The central strategy in travel hacking is to collect award points and frequent flyer miles, and use them to “pay” for a flight, hotel, or travel experience in one way or another. Think of award points as currency just like the money in your pocket.

There is no universal definition of travel hacking, but I think a good starting point is this:

Travel Hacking is the process of lowering the cost of travel through a variety of techniques, strategies, and options including acquiring frequent flyer miles and other award points, and then using them in the most efficient way possible.

Even to me, hearing the phrase travel hacking conjures up negative connotations. It sounds a bit crude and almost childish, but in the end it’s just a phrase used to describe saving money and maximizing opportunities for travel. An easy way to put travel hacking into context is to ask yourself some basic but related questions. Have you ever:

- Used a rebate or coupon to lower the price of an item before a purchase?

- Signed up for deals, or promotions via email?

- Participated in the loyalty rewards program at any clothing stores, coffee shops or supermarkets?

- Gone to multiple websites to compare prices between merchants?

- Used a credit card for a purchase because it saves you money or earns rewards of some kind?

- Bought something on sale, jumped on a ‘buy one get one free’ deal or spent money on a similar promotional offer that ultimately saved you money?

Of course, everyone can answer “yes” to at least one of these. Travel hacking is similar because it offers consumers ways to lower the cost of travel, but also provides opportunity for a host of other positive possibilities.

Costs

Travel Hacking and the collection of (award) points are not free and have a cost. At the very least that cost is your time pursuing earning miles and points through a mattress run, mileage run, special promotion. The cost also includes any taxes and fees associated with an airline award ticket, or hotel redemption. I value my time and don’t like to waste it. I also value my effort, and many people underestimate the effort it takes to collect points on a mass level. On a micro level, points collecting is simple; but on a larger macro level, it becomes more complex, and usually involves significant time, resources, and organization.

The higher level of points accruing you strive for, the greater the need to keep track of the related information (like credit card account details balances, statement dates, payment dates, credit utilization, checking account balances, etc.). After all, how do you know how many points you have unless you are actively tracking your accounts?

Consumers, Norm, and Outliers

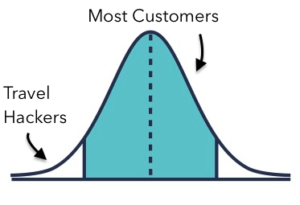

In statistical terms, most people in transactional systems operate in the middle, meaning they act or produce similar results. In statistics, they would be the interquartile range (IQR) or mid spread. They are the fish that make up most of the fisherman’s net, and the big shaded area in the bell curve image shown here. I, and others that collect points like me, are the small areas on the outer edges of the bell curve, or outliers in the system.

In statistical terms, most people in transactional systems operate in the middle, meaning they act or produce similar results. In statistics, they would be the interquartile range (IQR) or mid spread. They are the fish that make up most of the fisherman’s net, and the big shaded area in the bell curve image shown here. I, and others that collect points like me, are the small areas on the outer edges of the bell curve, or outliers in the system.

Outliers play the game and find our way around the awards and transaction maze in a different, and sometimes much different, way than nearly all of the others involved.

At store checkout lines I see people pay in cash, often in large amounts, use debit cards, or even write checks. I remember when I was one of those people, but now I feel a bit nauseous when I see it happen. The reason: those methods of paying really aren’t accruing rewards for people, but they are helping banks and other companies increase their profit. There’s a simple phrase that I abide by: Use Cash, Loose Cash. I am rewarded in some way for nearly every single transaction that I make, and always try and find the most efficient and maximum reward option possible.

Moral Awareness and Ambiguity

Is travel hacking ethical or moral? There are questions of morality, right and wrong on all sides of the system. In the end, I believe everything comes down to choices and transactional freedom. The companies have the freedom to create and manage programs that entice consumers but that also deliver financial returns and allow them to remain competitive and prosper. In turn, consumers have freedom to accept and decline those offers.

I think it’s also important to point out that there aren’t moral standards and fairness on just one side of the equation when it comes to travel and travel hacking:

- Do you think it’s fair and ethical for airlines and hotels to charge 3-5 times the normal rates on some flights and rooms?

- Is it fair for airlines to offer a price for a flight then not honor those prices?

Is it fair for airlines to oversell a flight then kick off passengers at will so that the flight is completely full? - Is it fair for credit card companies to charge 20%+ interest rates on credit cards?

- Is it fair for airlines to charge passengers over $500 for a fuel surcharge tax for a single flight when gas prices are at the lowest in over a decade?

- Is it fair for airlines to charge customers substantially more for the shortest and most efficient flight routing and significantly less for add on segments that actually make the flight longer?

- Is it fair that some airlines don’t show all award space to frequent flyer customers or offer no award seats for months to customers who have earned those benefits?

- Is it fair for airlines to oversell flights then remove passengers, even by force, for both paid and frequent flyer tickets?

These examples might not be fair, but they are legal. And so is travel hacking. Some aspects of travel hacking (such as manufactured spend) do skirt and sometimes cross some rules and restrictions that banks have put in place to deal with threats to their profit models. Some people cross those lines, some don’t, and others walk on or around that line. But for most people who use credit cards and other basic methods to earn rewards, bank rules and policies are not an issue. Each entity in the rewards system has rules and restrictions that they abide by. That part is not in dispute, but morality, or what is right, just and fair is largely ambiguous.

Points Bloggers

There are now unprecedented relationships between banks and blogging websites that blur the line between travel hacking and business relationships. By now most people have seen Capital One and other big bank commercials with celebrities promoting rewards programs like Chase’s Ultimate Rewards and even displaying quotes from notable points blogs as part of the advertisement. All the big points bloggers have big banks as “advertising partners” on their websites, hocking credit card applications while at the same time giving “unbiased” credit card reviews and advice. It’s kind of like a company that’s had it’s IT infrastructure broken into by internet hackers and then promoting the hackers with a commercial.

What does impact a system is when there are more and more people playing the game in a different way than it was designed. I see articles in Rolling Stone, interviews on CNN, guestspots on radio shows, and so forth talking about collecting points and miles for ‘free’ travel. The more people participate as outliers in the system, the less those results become rare, and the more the system is apt to change to deal with the changing market. That is what is happening now in the points and miles hobby – and in more regularity and severity than in years past. Travel hacking is not a secret anymore, and is much more mainstream than it ever has been.

Travel Hacking Impacts on the System

I am not “scamming the system” nor am I even close. In short, I couldn’t impact the system if I wanted to. It’s not even accurate to use a David vs Goliath comparison to describe a person like me influencing the systems that have been set up. I’m more like a kernel of corn, from a cob of corn, in a field of 10,000 acres of corn. I am simply participating in a large group of systems and an array of offers and transactions. I am a participant systems that have been planned and derived by some of the largest and most powerful banks, airlines, hotels, and other related companies in the world.

The systems, from credit scoring to ways to accumulate nearly free travel, are flawed. I, and others like me, simply participate in these systems in a different, and sometimes much different, way than most people do. The way most people participate is by generally doing what banks and other companies want, and have designed for, them to do. Systems, especially those that come from large publicly held corporations, are designed to bring in the most amount of money and profit possible. It’s like a large net cast over the bow of a ship to catch fish. The net will catch most of what the fisherman wants, but it also catches some things that they didn’t anticipate, like some crabs, shark, or jellyfish. The analogy was rough, but I think you get it.

Travel hackers find gaps in rules and restrictions and maximize returns in a number of ways, but the main difference between them and the people who don’t travel hack is simply information that leads to different choices.

The companies involved in issuing and redeeming points are very well aware of people who collect them en masse in order to travel for less. Some examples of that awareness include:

- Airlines consistently raising award price levels (for example, flying to South Africa from the US in business class on US Airways cost 110k miles in 2014 and the next year it cost 150k).

- Hotels increasing award prices (for example, Hilton’s award program devaluation by 90% for some categories in 2013).

- Banks placing new restrictions and rules for credit cards (American Express, CITI, and Chase have all dramatically increased restrictions on points related credit cards and applications for them over the past two years).

- Alaska Airlines making specific references to “travel hackers” in public statements as a justification for increasing its award chart in March 2016.

It’s generally a win-win situation all the way around as airlines sell miles for profit, banks buy miles to use for credit card sign ups, other companies buy points and miles for promotions, and customers get miles for doing business with those companies. In reality, travel hackers are a small subset players in the overall system.

Airlines are also earning upwards of 50 percent of their yearly income from selling miles to credit card companies. The selling of miles are also relatively immune to economic cycles, providing banks with a nice revenue cushion in a downturn. According to recent Bloomberg article, Delta Air Lines Inc., has revenues of over 300 million per year from its partnership with American Express and expects that figure to grow to roughly $4 billion by 2021.

A substantial percentage of miles that airlines and banks give to customers are also never used. According to a June 2016 article in the Financial Times, American Airlines had approximately 854 billion unclaimed miles from its Advantage program and the German carrier Lufthansa had 211billion unused. In 2013 the DailyMailUK stated that there were an estimated 14 trillion unused airline frequent flyer miles and that roughly half of the flyers don’t actually redeem the rewards they earn.

Travel Hacking and the Downstream Effects

The costs for award programs are being placed on those who do and do not have rewards. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, households that don’t pay with rewards credit cards lose an average of $50 each year, while households that do pay with these cards gain an average of $240. There are also transactional fees from credit cards in general (including rewards cards) that are rolled into purchases like interchange, terminal, gateway and other fees that add additional costs to everyday purchases. So whether you agree with travel hacking or not, you’re probably involved in paying for the system that they try and maximize. If you’re already paying for something, doesn’t it make more sense to try and get something in return?

The biggest moral concern that I have about the current trajectory of travel hacking is the effect that points and miles enthusiasts are having on others who are not actively engaged in mass points and rewards collection. Travel hacking via points and miles causes artificial inflation, or causing award redemption prices to move higher and faster than they normally would. That inflation makes it more and more difficult for people who aren’t actively participating in the hobby to reach.

Points and miles inflation is essentially creating a points and miles disparity between those who are and are not engaged in travel hacking. As more and more points and miles are needed to redeem for nearly free travel, the people tied into the points game can still achieve award redemptions, although possibly not as many or as quickly or as easily as in the past. However, people not active in travel hacking are faced with a much steeper, and often impossible, ladder to reach those same levels they once could. The opportunity cost of not engaging in travel hacking is becoming larger and larger as time passes and award prices rise.

I’m not particularly worried about travel hackers being able to keep up with rising award prices. They find ways to max out purchases, follow new trends and methods to take advantage of openings that might be there. But people for those who don’t the mountain for nearly free travel is becoming much steeper. I’ve attended national points and miles seminars, local meet up groups in the city that I live in, read thousands of posts online, but I’ve never heard of anyone talk about the downstream consequences for non-travel hackers.

But not everyone who knows about travel hacking wants to engage and participate. I’ve offered assistance to help many friends and relatives to allow them to travel more and for less money. Some have taken me up on my offer, but many have not had much of an interest. So even though help is there, it doesn’t mean people will always go that way.